Safe patient transfer techniques are the essential skills required to move an individual with limited mobility securely from one location to another. Executing this correctly involves a thoughtful combination of preparing the environment, communicating clearly, and using proper body mechanics to prevent injury to both the caregiver and the patient. The primary objective is always a smooth, controlled movement that minimizes physical strain and eliminates the risk of a fall.

The Blueprint for Every Safe Transfer

Before initiating any movement, such as helping someone to stand or pivot, the preparatory work is crucial. A successful, injury-free transfer is not a display of strength but a result of careful planning and a clear strategy. Neglecting this groundwork is a common cause of preventable accidents, turning a routine task into a hazardous situation.

Consider the physical space as an integral part of the process. The first step is to establish a clear "transfer zone." This involves removing all potential obstacles between the starting point and the destination. Move aside area rugs, secure electrical cords, and clear away any clutter. Ensure the area is well-lit so both you and the person you are assisting can see clearly.

Assessing the Person and the Plan

Once the environment is prepared, your focus shifts to the individual. A brief assessment is non-negotiable. Ask simple questions to confirm they are alert and capable of following instructions. An individual experiencing dizziness, pain, or confusion is at a significantly higher risk during a transfer.

You must also realistically evaluate their physical capabilities. Can they bear any weight on their legs? Can they use their arms to push up from a seated position? This quick evaluation determines the level of assistance required and helps you select the safest transfer technique. Once you have a plan, communicate each step in a calm, clear voice before initiating movement.

"Okay, I'm going to help you move to the wheelchair now. On the count of three, we'll rock forward and stand up together. Ready? One... two... three."

This type of clear communication eliminates surprises and empowers the person to participate in their own movement, which is a key component of a secure transfer.

Protecting Yourself: The Caregiver

A frequently overlooked aspect of a safe transfer is caregiver self-protection. Musculoskeletal injuries are extremely common among caregivers. Studies indicate that nursing assistants and registered nurses experience some of the highest rates of work-related injuries, predominantly from patient handling. The solution lies not in brute strength, but in the application of proper body mechanics.

Adhere to these core principles to protect your back and joints:

- Get a Wide Stance: Place your feet shoulder-width apart to create a solid, stable base.

- Bend at Your Knees and Hips: Never bend from your waist. Squat down, keeping your back straight.

- Keep Them Close: Hold the person you are assisting as close to your body as possible. This centers the weight and reduces strain on your back muscles.

- Pivot, Don’t Twist: When turning, move your feet. Twisting your spine while lifting is a primary cause of back injuries.

A proactive approach to fall prevention is fundamental to any transfer plan. Understanding and implementing effective strategies for preventing falls is essential for a safe environment. For more complex scenarios that may require specialized equipment, our detailed guides on patient lifts offer a wealth of information.

Putting Safe Transfers into Practice

Theoretical knowledge is important, but true confidence is built by mastering hands-on, everyday transfers. The core principles—preparation, assessment, communication—are the foundation. However, it is in real-world situations, such as moving from a bed to a wheelchair or navigating a confined bathroom, that technique truly demonstrates its value.

This is not just about lifting; it's about learning to guide, pivot, and work with the person's momentum. This approach makes the entire process smoother and less physically demanding for everyone involved. Let's explore the most common transfer scenarios.

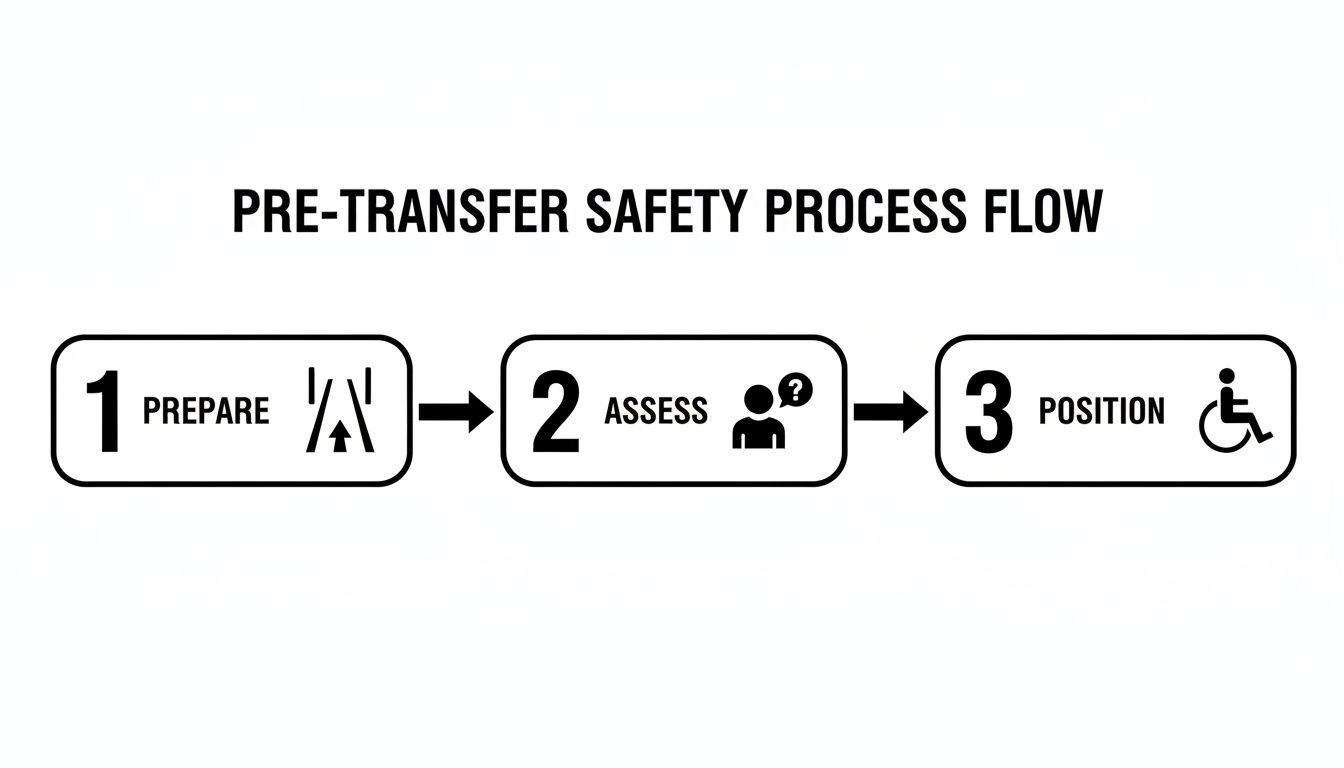

This simple workflow illustrates the pre-transfer process in three essential phases, emphasizing that the physical move is the final step in a carefully planned sequence.

The process begins with preparing the space and assessing the individual's readiness, well before the physical lift occurs.

From Bed to Wheelchair: The Stand-and-Pivot

The bed-to-wheelchair transfer is one of the most frequently performed maneuvers. The goal is to achieve a fluid "stand-and-pivot" that relies more on coordination than on physical strength.

First, prepare the environment. Position the wheelchair at approximately a 45-degree angle to the bed, facing the intended direction. Critically, lock the wheelchair brakes. Swing the footrests out of the way or remove them entirely to ensure a clear path.

Next, assist the person to sit on the edge of the bed with their feet flat on the floor, wearing non-slip footwear.

Now, position yourself as their anchor. Stand directly in front of them with your feet shoulder-width apart for a solid base. Bend at your knees and hips—never at your back. Instruct them to place their hands on your arms or shoulders for support. A crucial safety tip: never allow them to hold onto your neck, as this can pull you off balance and risk injury to both of you. A transfer belt is an invaluable tool here, providing a secure grip point around their waist.

On the count of three, guide them through the motion verbally. "Okay, on three, we're going to rock forward and stand." Coach them to lean forward and push off the bed with their hands, using that forward momentum. As they begin to stand, guide them upward, using your knees to block theirs from buckling. Once they are standing, pivot on your feet—do not twist your back—to align them with the wheelchair. Ask them to reach back for the armrests, and then gently guide them into a seated position.

Navigating the Wheelchair-to-Toilet Transfer

Bathrooms often present challenges due to their confined spaces and hard surfaces, which increases the risk associated with transfers. The key is to use the environment to your advantage.

If possible, install sturdy grab bars next to the toilet. These are invaluable aids, offering a stable point for the person to pull themselves up and maintain balance. A raised toilet seat or a toilet safety frame can also significantly help by reducing the distance they need to lower themselves.

Position the wheelchair as close to the toilet as possible, again at a slight angle, and lock the brakes. The transfer technique is similar to the stand-and-pivot, but with greater reliance on the grab bars. Encourage the person to use one hand to push off the wheelchair armrest while reaching for the grab bar with the other.

Your role is to be a guide and stabilizer, not the primary lifter. By using leverage and available aids, you can transform a potentially difficult transfer into a much safer, more manageable task.

Conquering the Car Transfer

Getting in and out of a vehicle requires a modified approach. Before bringing the person to the car, prepare the passenger area. Push the seat all the way back and recline it slightly to create maximum space.

Position the wheelchair parallel to the passenger seat and lock the brakes. The initial movement is the familiar stand-and-pivot. However, the next step is to have them turn and sit on the edge of the car seat with their legs still outside the vehicle.

Once they are securely seated, you can assist them in swinging their legs into the car one at a time. A helpful tip is to place a plastic garbage bag on the car seat beforehand; the slippery surface reduces friction and makes sliding back into the seat much easier.

When manual transfers become consistently unsafe or strenuous, it is time to consider mechanical aids. A landmark 1999 "zero-lift" program in healthcare facilities demonstrated their effectiveness. By implementing mechanical lifts, facilities achieved a 66% reduction in staff injury rates and a 78% decrease in lost workdays. This provides compelling evidence for home caregivers that such equipment is a proven safety tool, not a luxury. You can explore the full patient transfer safety research.

Remember, every transfer can be adapted based on the individual's ability to assist. The more they participate, the safer the process is for everyone. Always communicate, move with intention, and prioritize proper technique over physical strength.

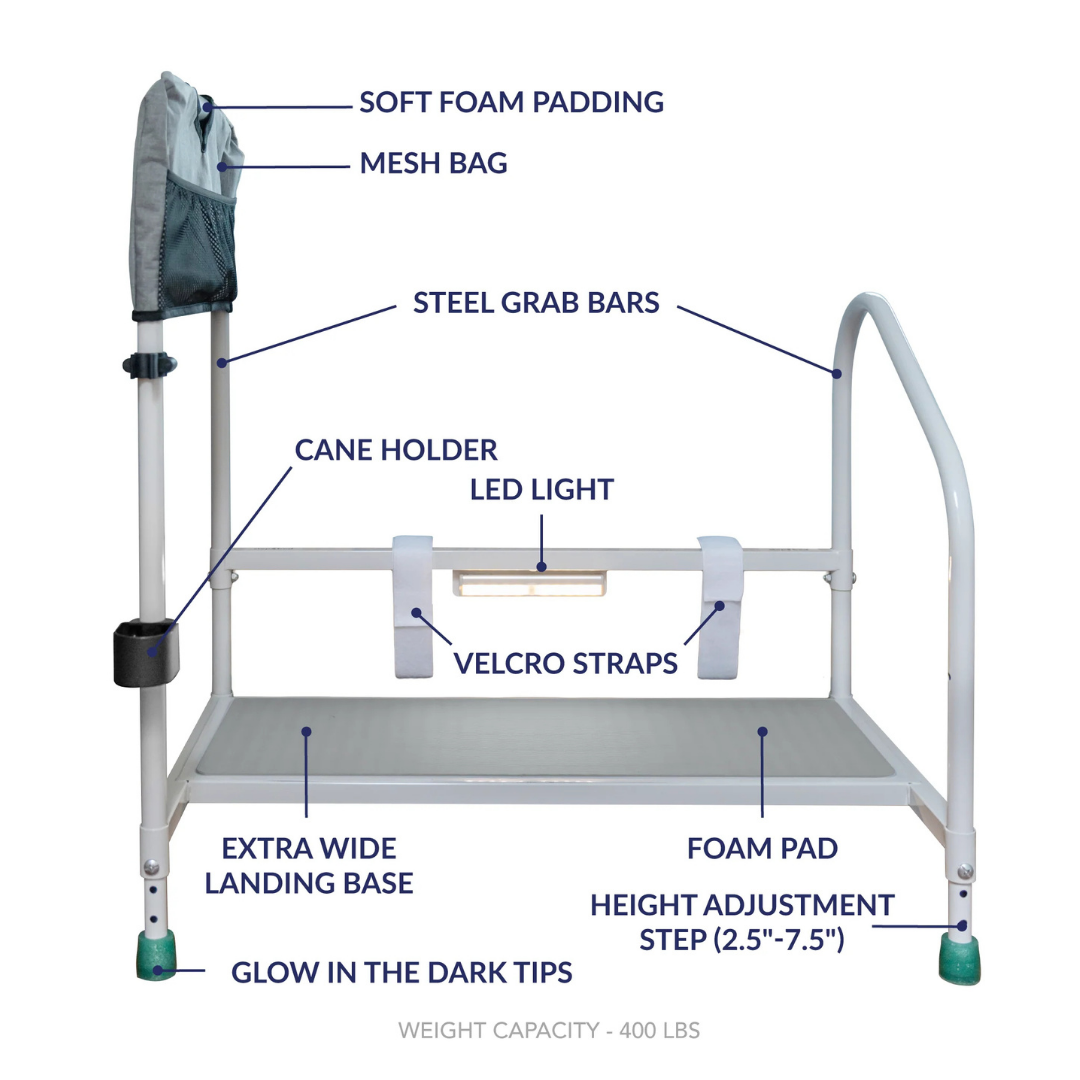

Using Equipment to Reduce Risk and Strain

Relying solely on physical strength for patient transfers is an unsustainable and dangerous strategy. It can lead to caregiver burnout, back injuries, and an increased risk of falls for the person being cared for.

Fortunately, a wide range of durable medical equipment is designed specifically to make these movements safer and less physically demanding. Learning to use these tools is not just beneficial—it's one of the most effective safe patient transfer techniques you can adopt.

These aids do more than simplify the task; they fundamentally alter the physics of a transfer. They shift the action from a risky lift-and-carry motion to a controlled, guided movement. This protects your back while providing a more stable and reassuring experience for the person being moved.

The Gait Belt: Your Essential Partner

The gait belt, also known as a transfer belt, is an essential tool for every caregiver. This simple device is a sturdy belt that buckles around the person's waist, offering a secure handhold.

Grabbing onto a person's arms or clothing is unstable and can cause skin tears or bruises, particularly on fragile skin. A gait belt mitigates this risk.

To use it correctly, wrap it snugly over their clothing at the waist. You should be able to slide two fingers between the belt and their body—any looser is insecure, any tighter is uncomfortable. Fasten the buckle securely in the front. During the transfer, grip the belt from underneath with both hands. This provides a firm, upward hold and direct control over their center of gravity, facilitating smoother pivots and guided standing.

Bridging Gaps with a Slide Board

A slide board is a smooth, rigid board used to create a bridge between two surfaces, such as from a wheelchair to a car seat or a bed to a commode. It is an ideal tool for individuals who have good upper body strength but cannot bear weight on their legs.

The setup is key to using a slide board effectively.

- Position the wheelchair as close as possible to the destination, ensuring both surfaces are at a similar height.

- Always lock the wheelchair brakes.

- Assist the person in leaning away from the direction of movement so you can tuck one end of the slide board under their hip.

- The other end of the board should rest securely on the target surface.

From this position, the person can use their arms to slide across the board in small, controlled movements while you provide stability and guidance. This technique completely eliminates the need for lifting.

Using assistive devices correctly is a cornerstone of safe patient handling. Research has shown that even with "proper" body mechanics, manual lifting is a leading cause of musculoskeletal disorders among caregivers. Equipment like slide boards and transfer belts are proven replacements for manual effort, not just supplements to it.

Stepping Up to Mechanical Lifts

For individuals who are fully dependent and unable to assist with transfers, a mechanical lift is the safest option. These devices perform all the heavy lifting, protecting caregivers from potentially serious back injuries. Two main types are commonly used.

-

Hoyer Lifts (Floor Lifts): These are portable, wheeled lifts. A special sling is positioned under the person and then attached to the lift's boom. Using a hydraulic or electric mechanism, the lift gently raises, moves, and lowers the individual. Their portability allows them to be used in different rooms as needed.

-

Ceiling Lifts: These systems are permanently installed on a track mounted to the ceiling. They operate with a sling similar to a Hoyer lift but provide a more seamless transfer within a single room, as there is no base to navigate around furniture. They are an excellent, though more permanent, solution for rooms where transfers occur frequently.

Proper training is required to select the right lift and sling, and regular equipment inspections are essential. You can learn more by reading our guide on the guidelines for identifying deteriorated patient lift slings to ensure all equipment remains in safe working condition.

The benefits of this equipment extend to the patient as well. The adoption of mechanical aids has been shown to reduce patient falls by up to 35% in some care facilities and improve comfort by minimizing skin tears and pressure ulcers. Studies confirm that such equipment not only reduces injury risks but can also enhance patient mobility and shorten hospital stays. Discover more about these findings on patient safety and mobility. By choosing the right aid, you can transform challenging transfers into manageable and secure procedures for everyone involved.

Choosing the Right Transfer Aid for Your Needs

The appropriate tool depends on the person's abilities and the specific transfer being performed. This table provides a breakdown of common options to assist in your decision-making.

| Transfer Aid | Best For | Patient Mobility Level | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gait Belt | Assisting with standing and pivoting; short-distance transfers (e.g., bed to chair) | Can bear some weight; needs minimal to moderate assistance | Provides a secure handhold, preventing caregiver strain and improving stability. |

| Slide Board | Seated transfers between two surfaces of similar height (e.g., wheelchair to car) | Cannot bear weight but has good upper body strength and trunk control | Eliminates the need for lifting, allowing the patient to assist in the transfer. |

| Hoyer Lift | Full-body transfers for non-weight-bearing individuals (e.g., bed to wheelchair) | Fully dependent; cannot assist with the transfer | Does all the heavy lifting, protecting the caregiver from serious injury. |

| Ceiling Lift | Frequent transfers within a single room (e.g., bedroom, bathroom) | Fully dependent; requires maximum assistance | Offers seamless, one-person operation without navigating a bulky base. |

By matching the equipment to the individual's needs, you create a safer environment that promotes dignity for the patient and longevity for the caregiver.

How to Safely Manage a Transfer After a Fall

Witnessing a fall can be distressing, and the natural instinct is to immediately help the person up. However, the most important action is to pause, remain calm, and assess the situation before attempting any movement.

Improperly lifting someone after a fall can turn a minor incident into a serious injury for both of you.

First Steps: Assess Before You Assist

Before attempting to move the person, conduct a thorough assessment. Is the person conscious and responsive? Ask simple questions, such as their name, to check their alertness.

Visually inspect for obvious injuries. Look for bleeding, swelling, or limbs at unnatural angles. Ask them directly, "Where does it hurt?" If they report head, neck, or back pain, or if they are unresponsive, do not move them. Call for emergency medical assistance immediately.

If they appear uninjured, are clear-headed, and feel they can assist, you may proceed with a carefully planned transfer.

The Chair Leverage Technique

For an individual who has some strength and can follow instructions, using a sturdy chair for leverage is one of the safest manual methods.

Place a stable chair, such as a solid dining chair, directly in front of them. Encourage them to first get onto their hands and knees and then crawl toward the chair.

Once they are close, guide them to place both hands firmly on the chair's seat. Coach them to bring one leg forward, planting that foot flat on the floor to create a lunge position. From there, they can use the strength in their arms and forward leg to push themselves up, while you provide balance and support.

Your role here is to be a spotter and a guide, not the lifter. The person on the floor should be doing the majority of the work, using the chair as their main point of leverage.

When to Use a Two-Person Assist

If the person requires more assistance than the chair method allows but can still bear some of their own weight, a two-person assist is a much safer option than attempting it alone.

One caregiver should position themselves behind the person, reaching under their arms to get a secure grip on their forearms (a "handshake" grip is effective). The second caregiver stands in front, facing the person, ready to guide their legs and feet.

Clear communication is essential. Agree on a verbal cue, such as counting "one, two, three, up," to ensure you lift in perfect sync. This coordinated effort distributes the weight evenly and maintains control, significantly reducing the risk of strain or another fall.

When manual methods are too risky, specialized equipment is invaluable. The Bounce Back Fall Recovery Patient Lift is specifically designed for these situations, allowing a single caregiver to safely lift a person from the floor without manual strain. Knowing when to use a mechanical aid instead of a hands-on technique is a critical safety decision.

Knowing Your Limits and When to Seek Help

One of the most important safe patient transfer techniques is not a physical action but the judgment to stop before you begin. Recognizing when a transfer is too risky to attempt alone is a skill that protects both you and the person you care for from serious injury. Pushing through exhaustion or uncertainty can lead to accidents.

Be honest with yourself about your physical and mental state. If you are feeling tired, rushed, or unwell, attempting a difficult transfer significantly increases the risk of a mistake. If you have any doubt about the correct procedure for a specific situation, pause and seek assistance.

Patient-Related Red Flags

Often, the person you are assisting will provide clear signals that a transfer is not a good idea. Pay close attention to these warnings, as they indicate the need to stop and re-evaluate your plan.

You should stop and get help if the person:

- Shows a sudden change in condition: This includes new dizziness, confusion, nausea, or a sharp increase in pain. These could be signs of a medical issue that makes movement dangerous.

- Verbally or physically resists: If they express fear, report excessive pain, or actively push you away, do not force the transfer. Forcing the issue is unsafe and erodes trust. Respecting their refusal is essential for dignified care.

- Seems unusually weak or unstable: If they are suddenly unable to bear weight or seem limp when they normally assist, a manual transfer should not be attempted.

A transfer is a partnership, not a one-sided action. When one partner is unable or unwilling to participate safely, the entire plan must be halted. Proceeding against these red flags can turn a routine move into an emergency.

When Professional Help Is Non-Negotiable

Beyond your own limitations and the person's immediate condition, certain medical situations make transfers off-limits without professional guidance. For example, following a recent hip replacement or major spinal surgery, specific movement precautions must be followed to prevent dislocation or serious injury. In such cases, always adhere to a physical therapist’s instructions.

Attempting complex transfers alone is a known hazard, which is why many hospitals utilize dedicated "lift teams." The impact is significant; one hospital study found that implementing a lift team reduced patient transfer injuries among nurses by 65% in a single year. Prior to this, the facility incurred over $600,000 annually in injury-related costs. You can read more about the benefits of specialized transfer teams.

This data offers a crucial lesson for home caregivers: knowing when to call for backup is a sign of strength. Whether it means asking a family member for a two-person assist, hiring a home health aide, or consulting a physical therapist for hands-on training, seeking help is always the smartest and safest choice.

Common Questions About Patient Transfers

Even with proper training, questions and challenging situations will arise. Having answers ready can turn a moment of uncertainty into confident action.

Here are some of the most common questions caregivers ask.

What Is the Single Most Important Thing to Remember?

If you take away only one lesson, let it be this: preparation and communication. These are the cornerstones of every safe transfer.

Before initiating a move, set the stage. Clear the path of hazards, ensure all equipment is secure, and, most importantly, talk the person through every step. A rushed transfer is an unsafe transfer. Taking an extra minute to communicate the plan reduces anxiety and allows them to assist to the best of their ability.

How Do I Know If I Should Use a Mechanical Lift?

This is a critical judgment call, and it is always better to be cautious. You should use a mechanical lift if you find yourself regularly lifting more than 35 pounds of a person's body weight.

It is also the only safe option if the person cannot bear any weight, is uncooperative, or if you feel any strain during a manual transfer. A lift is non-negotiable for certain conditions, such as severe osteoporosis or a recent fracture. If you are unsure, consult an occupational or physical therapist for a professional recommendation.

How Can I Reassure Someone Who Is Afraid of Being Dropped?

Fear of falling is a powerful emotion that must be addressed. Building trust through a calm and confident demeanor is your most effective tool.

- Narrate Every Action: Eliminate surprises by explaining each step before it happens. For example, "I'm going to place this belt around your waist now. It will feel snug, which means it's secure."

- Maintain Eye Contact: This simple act of connection demonstrates that your focus is on them and their well-being.

- Move Slowly and Deliberately: Fast, jerky movements can be frightening for someone who feels unstable. A smooth, steady pace helps them feel more secure.

Your calm and controlled approach will have a soothing effect, leading to a safer and more cooperative transfer.

A patient's fear is a legitimate barrier to a safe transfer. Acknowledge their feelings, move at their pace, and demonstrate safety through your actions. This approach transforms the experience from something to be feared into a predictable and secure routine.

For caregivers interested in the professional standards underpinning this type of person-centered support, exploring the diverse career pathways in health and social care can provide valuable context.

Are There Special Techniques for Bariatric Patients?

Yes, transferring bariatric patients requires specialized equipment, techniques, and often, more than one person. Manual lifting should be avoided entirely, as it poses a high risk of serious injury to both the caregiver and the patient.

Always use equipment specifically bariatric-rated for higher weight capacities, including heavy-duty mechanical lifts, specially designed slide sheets, and reinforced transfer boards. Even with the right tools, these transfers are almost always a two-person job. It is crucial to receive hands-on training from a healthcare professional before attempting to transfer a bariatric individual.

At DME Superstore, we know that having the right equipment is the cornerstone of safety and independence at home. From transfer belts and slide boards to state-of-the-art patient lifts and bathroom safety aids, we provide the tools caregivers need to perform transfers with confidence and dignity. Check out our curated selection of homecare essentials and find the perfect solution to make every day safer. Visit us at https://dmesuperstore.com to learn more.

Article created using Outrank